Artist of the Month

MAXIMILIEN LUCE

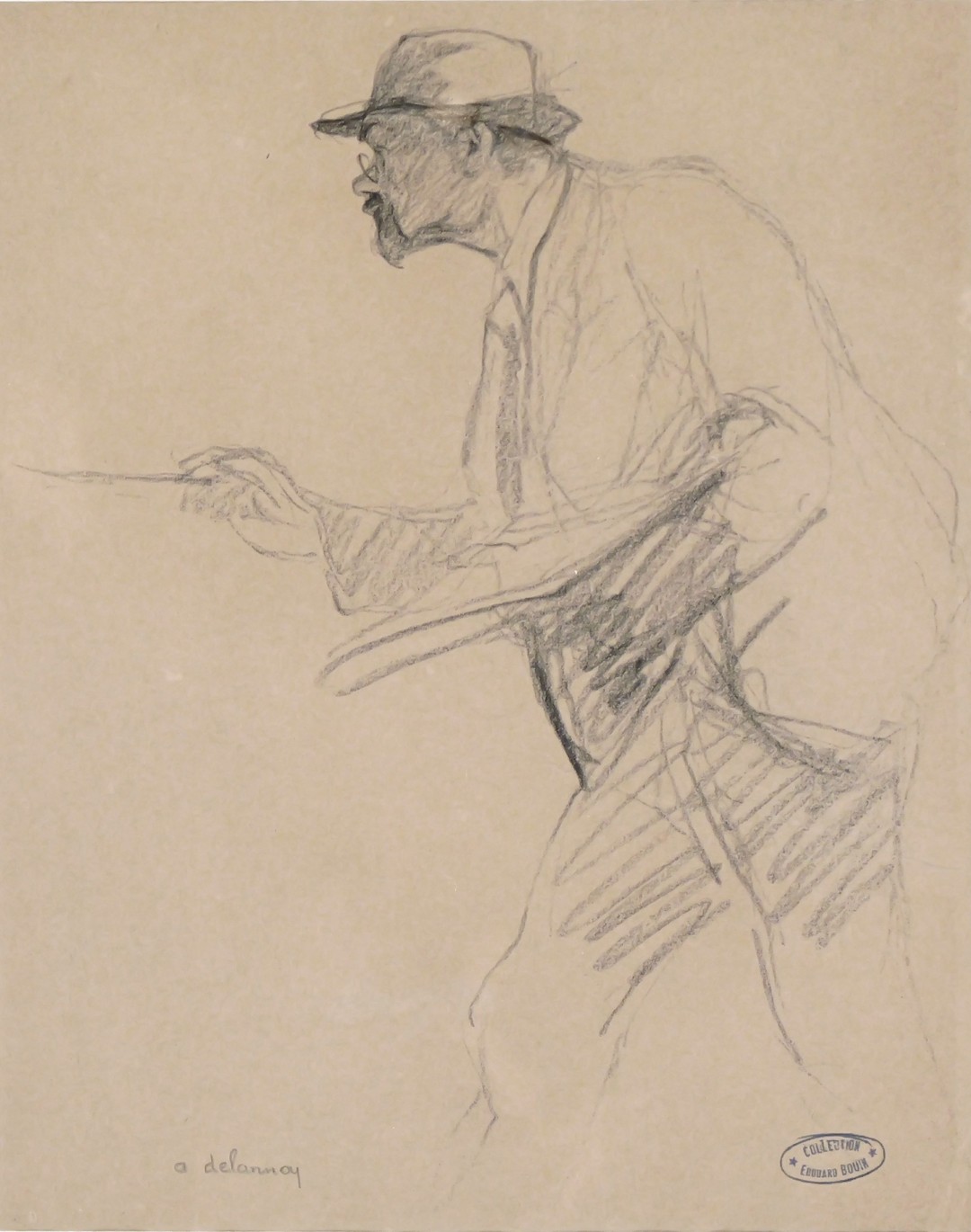

MAXIMILIEN LUCE WHILST PAINTING

Aristide Delannoy (1874 Béthume – 1911 Paris)

Pencil on Paper, 28,5 x 23 cm

Signed lower left: A. Delannoy, below right.: Stamped Edouard Bouin

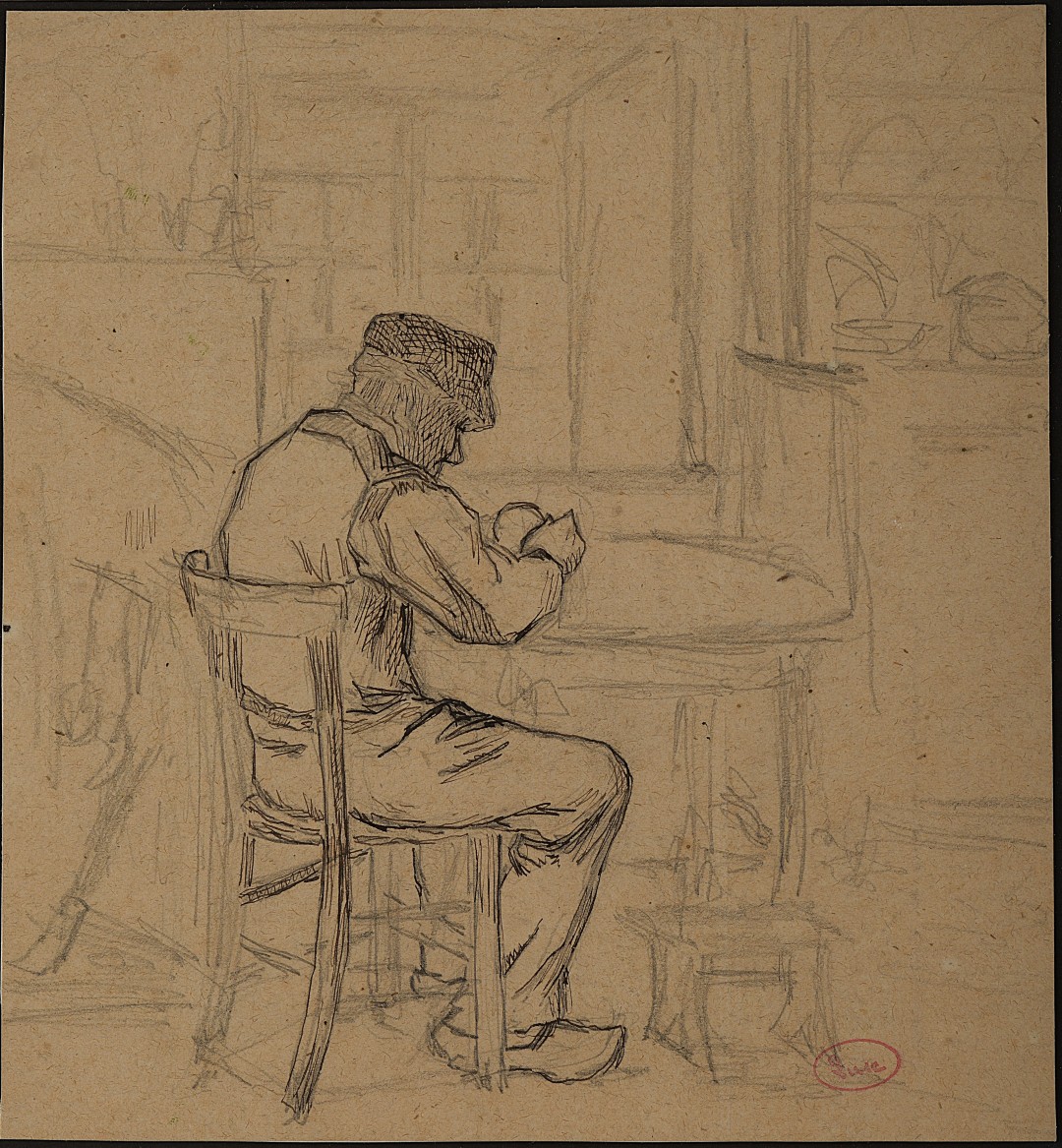

Man Wearing Wooden Shoes and Sitting at the Table

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

1876-78

Pencil and black ink on paper,

19,5 x 18,3 cm, Stamped Luce lower right

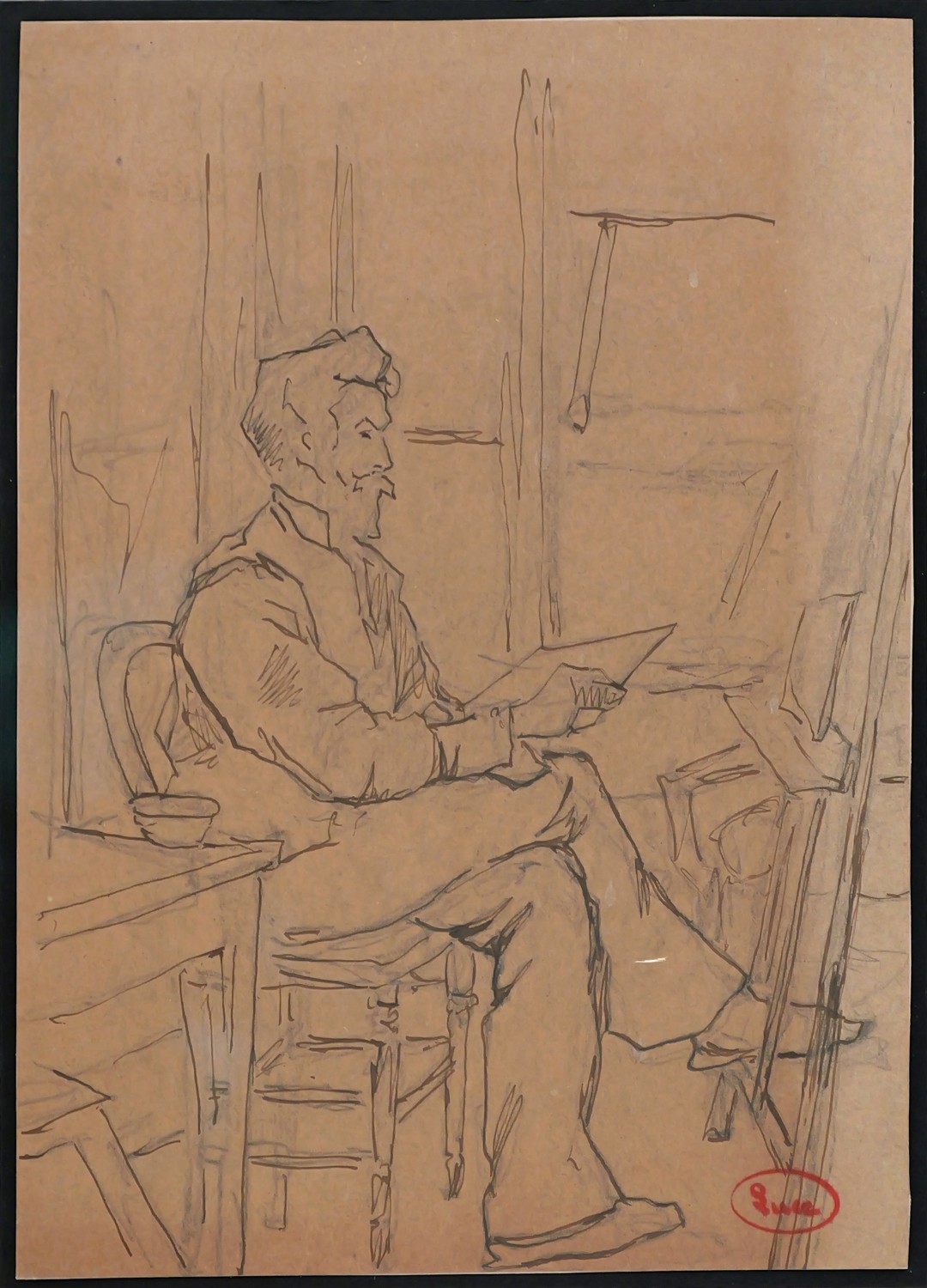

Artist in the Studio

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

1898

Pencil and black ink on paper, 18 x 12,8 cm, Stamped Luce lower right

Street Scene at Dusk

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

1890’s

Oil on Canvas, mounted on canvas board, 16 x 25,5 cm

Signed upper right: Luce

Provenance: Collection Jean Bouin Luce

Literature: Jean Bouin-Luce et Denise Bazetoux, Maximilien Luce, catalogue de l’œuvre peint, Bd. II, Édition JBL, Paris, 1986, Nr. 194, Ill. S. 55

Seine at Rolleboise

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

Oil on Cardboard, 23,5 x 41 cm, signed und dedicated lower left: A l’ami Finch, Luce

Exhibit: Riksförsbundet för bildande konst, Nr. 32

Tipp

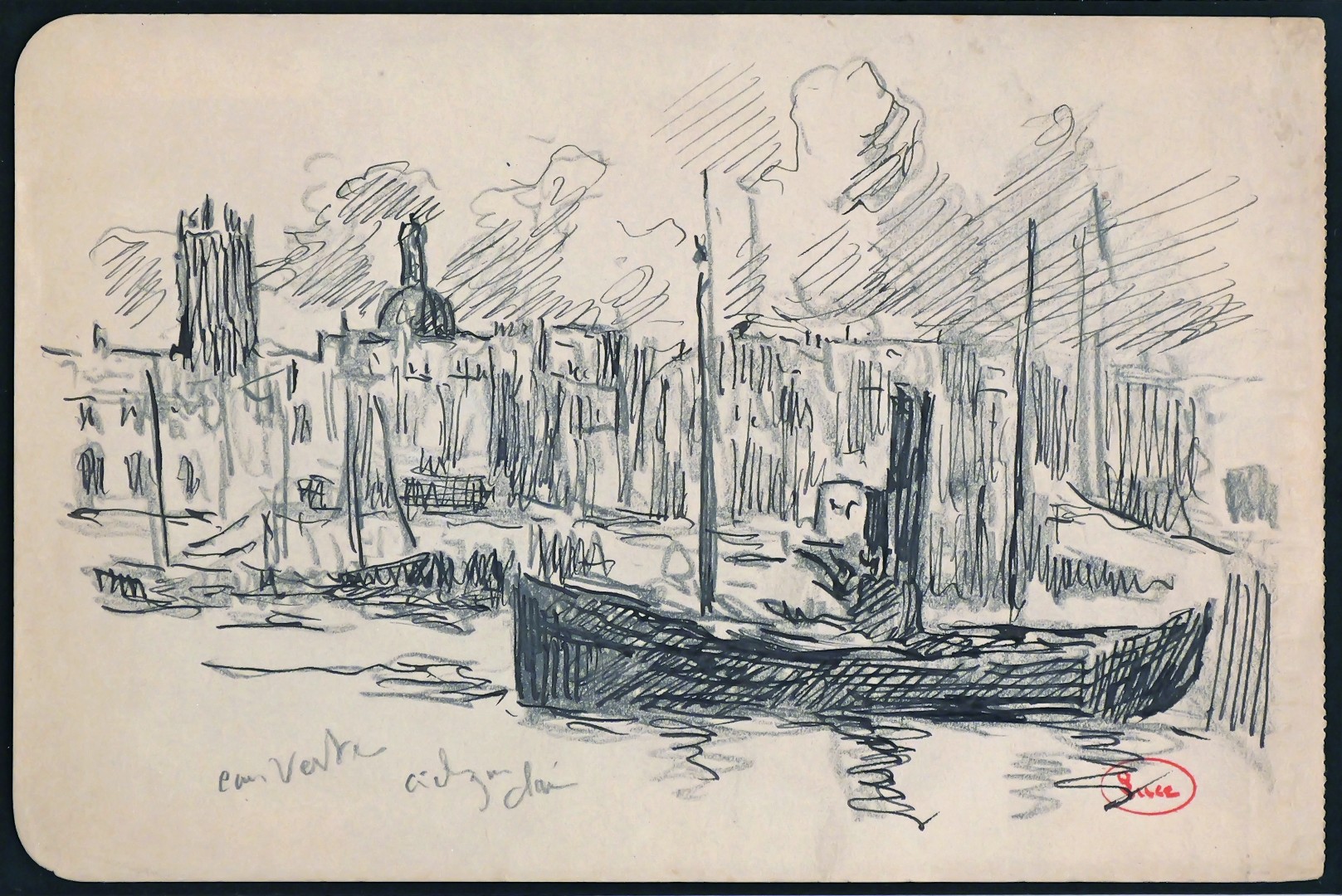

Steamboat in the Port of Dieppe

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

1922

Pencil and black ink on paper, 12,5 x 18.2 cm, Stamped Luce below right, Lower left: eau verte, ciel … clair

The Town of Rolleboise

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

Black ink and pencil on paper, 24 x 30 cm, Signed lower right: Luce

River bank

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

Black chalk on gray-green Paper, 20,5 x 25,5cm

Signed in Pencil lower left: Luce

,%20o.%20R.,%20PHHI5243a.jpg)

LYING MAN (STUDY FOR „DEAD SOLDIER“)

Maximilien Luce (1858 Paris – 1941 Paris)

Pencil on Paper, 16,6 x 25,6 cm

Stamped Luce lower right